Nearly Twenty Years Later, the Original Metal Gear Solid Still Has a Unique Atmosphere

Editorial by Maxwell N, Posted on May 24, 2017

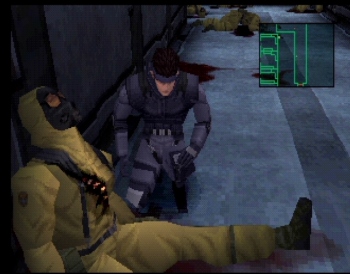

Praise for Metal Gear Solid is certainly not difficult to find. Since the day of the game’s release in 1998 on Sony’s PlayStation, it has been revered and raved about within nearly all forms of media possible. People have talked about its influence on the games that followed it, and how Hideo Kojima’s love for film and the desire to make games more like movies resulted in possibly the first true cinematic gaming experience. The story and themes of this game, such as the need for war, the responsibility of nuclear power, questioning reality, the philosophy of being a soldier and more have been talked about on and on for the past two decades. Rightly so.

Instead of lingering over the said and done, I want to talk about the aspects of MGS1 that, for me, make up the unique “atmosphere” of the game; impressions that have remained with me since the first time I ever played MGS1 right before the end of the last millennium and elements I am drawn back to when I occasionally replay the game. Some of these elements, I find, are not talked about as much or at least are deserving of a reiteration.

I’d also rather look at MGS1 and its atmosphere as its own game, with little reference to the franchise that came after it. For me, the game remains disconnected from what came after. It stands solitary.

If I try to conjure up a sort of generalized mental image of MGS1, the memories immediately come in shades of green and black. Sure, there are some other colors, like the blues of fluorescent lights, the whites of Alaska, and all the grays in-between. But the more time you spend in the game, greens and blacks remain prevalent. The world presented exists primarily in colors which remind me of a calculator or Game Boy screen, though I guess the theme was more-so based on computer terminals. And, unlike what you see in big budget movies today, the characters and environments are not bathed in a color-graded overlay. The color scheme in MGS1 actually makes up the world around you, with characters and places existing within it, instead of it being a lazy and gaudy splash all over the place.

The choice of colors and textures might have been born out of limitation, but led to the creation of a completely unique environment. I remember that, during my first play-through, it all looked otherworldly, like fantasy despite being realistic than other more cartoonish games I had been playing at the time. I could feel the isolation that Solid Snake was feeling, sneaking around a cold and unfamiliar map.

When huddled into the confined, minimal, green-and-black UI of the Codec screen, the colors present themselves the same way. Contact with HQ is disconnected, like it exists somewhere behind the scenes that you can never reach. Within the story, when you start to realize that HQ might be using Snake as a pawn as part of a massive government conspiracy, the Codec screen becomes a space even more confining than before, despite the fact that you start getting unauthorized calls and witness events that have an impact on the world outside.

A stealthy musical score, which doesn’t hide its synthetic quality, coupled with some organic sounds now and then, emphasizes all of this. And yeah, a lot has been said about the soundtrack in the past, but what really stands out in my memories is the few times when the score transitions into a sort of ambient BGM thing.

Now this might sound weird but, for me, the very first time Snake crawls into the air ducts, and the ambient sound of the ducts comes in, is a really memorable moment. What is that sound? Maybe it’s the ventilation system? In any case, that low rumble, with a rounded, rolling, industrial noise that phases through the left and right channels; it just grabs me and makes me really aware of the game’s world and where I am in it. It reminds me of ambient sounds in Silent Hill 1 and 2, where it’s hard to discern if the sounds are part of the score or a nearby machine. Right as you enter the “Comm. Tower”, there’s a similar moment, with synth sounds stinging in and out within a rumbling wind. Considering that the first time you hear it, it’s right before all hell breaks loose, having to fight your way through what seems like a hundred Genome soldiers (a.k.a spamming the stun grenade), it is a somewhat foreboding sound in retrospect. Once you enter the tower again, the sound makes you wary. Is something going to happen again? The suspense lingers around.

This guy found a way to read PlayStation Memory Cards with his mind! Sony executives hate him!

This guy found a way to read PlayStation Memory Cards with his mind! Sony executives hate him!I’m not sure if Psycho Mantis’s mind control music counts as an ambient score, as it is both part of the score and music playing within the world of the game. It for sure sets up the tone for events to follow. I remember playing, as a child, dying multiple times during the boss fight and having to walk up that hall, having Meryl being forced to be a puppet and so on. It imprinted that music in my mind, which I suppose is the point, but at the time it was just unsettling. Psycho Mantis directly intimidating you, the player, through the fourth wall, didn’t help make it any less spooky.

Despite all these themes working against optimism, and the game taking place in a hostile and uninviting location, the game breaks in and out of the fourth wall like this all the time. Both for the sake of humor, and for the sake of communicating with the player.

I remember it was an odd experience for the game’s characters to take turns talking to Snake, and then to the player, interchangeably. It stayed with me, and though I wasn’t sure about all the silliness at first, as an adult I have come to appreciate the cheesy humor more than ever. It takes a wink and a nudge to the player to an unprecedented extreme for the time. This would be annoying usually, but what makes it work is that when the fourth wall is broken by a character, the other characters do not acknowledge it. In that moment, that particular character is talking to you, the player, reminding you that you are needed in order to progress the story. Instead of breaking immersion, this actually serves to be a very engaging way for the game to convey its theme of questioning reality.

The words coming out of the mouths of the characters breaking the fourth wall are not their own, but rather messages from the writers and developers of the game. It’s as if the characters are possessed by the creators for a minute in order to communicate with you; like ghosts, this is the only way for them to reach your physical world directly. In my mind, the game is a partial comedy because of this. It’s like you are an actor in a movie, playing Solid Snake, and all the inside jokes are things shared by the cast and crew. Unlike other experiences, this time, you’re in on the joke. The comedy exists within the game but it exists outside of the main narrative; it is almost never acknowledged within the context of the story. It seems to exist for you alone.

Staying on this tangent of humor, some lines sound like they belong in a cheap thriller novel, though I am not honestly sure if some of them were meant to be funny (at one point, after shooting Liquid’s chopper down, Snake walks looking away from the fiery explosion, and says, “See you in hell…Liquid. That takes care of the cremation”). The cast of baddies is a bit goofy to say the least. While their ideologies, and sometimes lack thereof, are interesting and at times provocative, something about imagining these dudes hanging around the water cooler is outright hilarious. However, it all blends into the pseudo-80′s espionage movie feel of the game.

While the members of FOXHOUND at times talk like inferior versions of Saturday morning cartoon villains, they remain mysterious and appear to have deep backstories that we are not meant to fully know; this only adds to the charm. It’s like paths intersecting, for damaged people fighting their internal demons externally. But, you know, some of them might be able to use physic powers to control the DualShock’s vibration and read your memory card, or be able to tell if you are using auto-fire during torture. Or freeze you with their crow head tattoo powers… in order to read your bloodline? I am still a bit unclear on that one.

Regardless, you don’t need to know anything about the characters aside from what you can assume from their dialogue, and you can always listen to optional Codec conversations if you are inclined to learn more. That beats forced exposition any day.

Looking back at all of this, it becomes very obvious why I dislike any attempts to remake MGS1 and its locations. Like most art, once something groundbreaking has been created by a certain individual, or a team of individuals, that specific idea is bookmarked in history. MGS1 is an example of something happening at just the right time, with just the right people, at that specific point in time.

We have, years ago, covered just why The Twin Snakes is an inferior remake that, frankly, does not even come close to conveying what made the original game unique. If it aimed to be a different take on the game, it was certainly a pointless endeavor.

Shadow Moses did not feel the same, again, when it was fan-service-ly revisited in Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots. In the context of that game, sure, it was supposed to be different, but the environment felt more like a 3D graphic design student’s homework than the body of the actual place. It felt like a cruddy copy, not a true revisit. All it did for me was make me want to play MGS1 again, which I did in one of my many attempts to forget that MGS4 exists.

I consider MGS1 to hold a unique place in the history of art and video games. It’s not because it is a perfect game—far from it, actually—but it was one of the first games to actually use the medium to its fullest potential and invoke an actual atmosphere that truly made you feel like you entered another world. A very unique world, standing on its own, where I believe it stands to this very day.